If Change Is “Everyone’s Job,” Then No One Owns the Outcome

TL;DR: Shared ownership is often a mask for accountability gaps. When change is decentralized to the point of anonymity, decisions stall and "influence" becomes a poor substitute for authority. To succeed, organizations must stop treating change as a collective sentiment and start treating it as a governed function with clear lines of answerability.

1. The Myth of Collective Responsibility

Modern organizations love to claim that "change is everyone’s job." It sounds egalitarian, mature, and strategically aligned. It suggests a rejection of the old-school, command-and-control silos where a single department dictated the future. In a world of constant transformation, the logic goes, change is too big to belong to a single function. It must be shared.

Let’s grant that premise. Change is undeniably complex. It crosses functions and alters technology, processes, behavior, and identity. No single team can "do" change in a vacuum.

However, when a mandate becomes "everyone’s job," a second, more dangerous claim usually follows: If everyone owns change, then no one is fully accountable for the outcome. Responsibility diffuses, authority blurs, and the results become collective in theory but orphaned in practice.

2. When Collaboration Becomes a Cloak

At first, shared ownership feels like a feature. It reassures leaders they aren’t overburdening one group and flatters the organization by implying a high capacity for self-coordination.

But organizations don’t actually run on vague sentiments of shared ownership. They run on decisions, tradeoffs, and escalation. They require people who are empowered to say "yes," authorized to say "no," and expected to answer for the consequences.

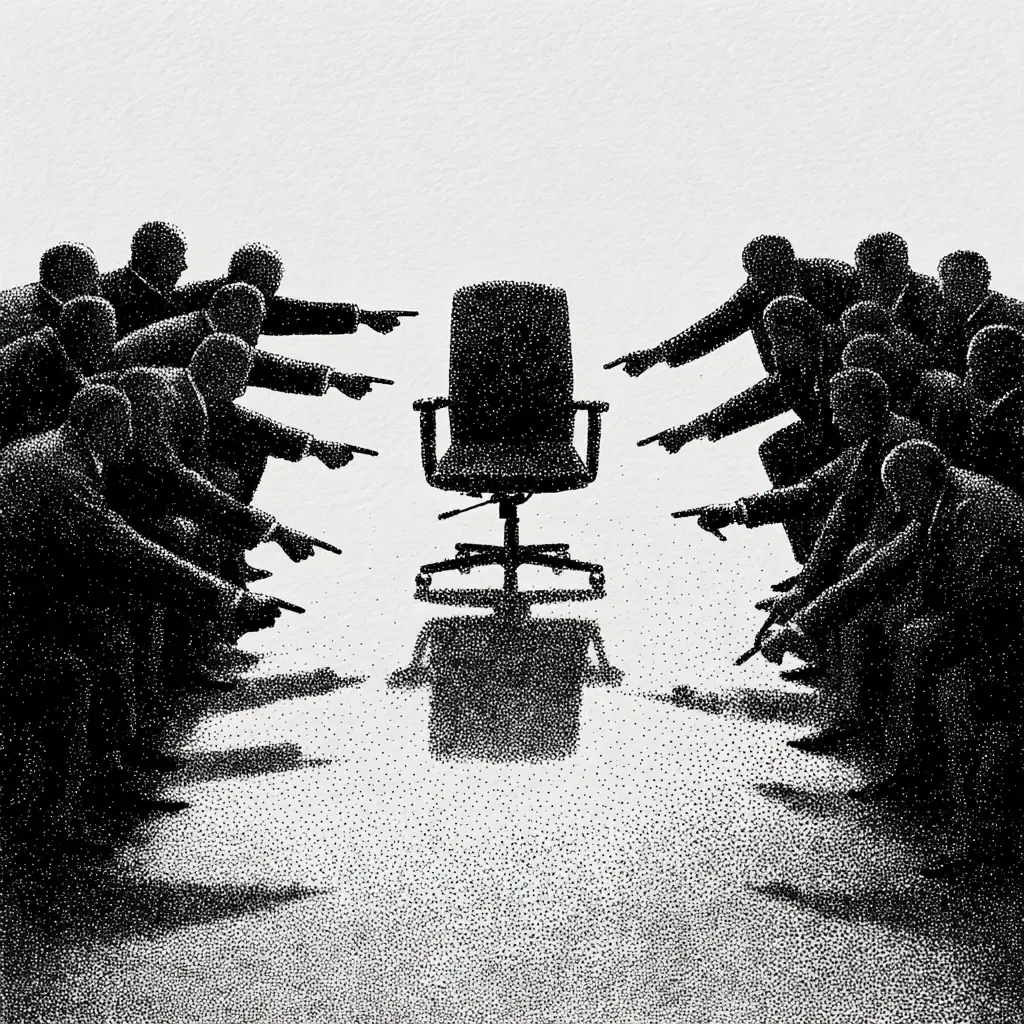

When change is declared everyone’s job, those expectations vanish. Consider the typical "stalled" transformation:

- The Business blames the change team for not driving adoption.

- The Change Team points to leaders who didn't model the behavior.

- Leaders claim employees weren't ready.

- IT asserts the system was delivered to spec.

Everyone was involved. No one is responsible. This isn't a failure of goodwill; it is a structural inevitability.

3. The "Influence" Trap

Change practitioners feel this most acutely. They are frequently told that "influence" is the new currency and that formal authority is outdated. They are asked to align stakeholders who do not report to them and drive adoption without levers.

The Hard Truth: Influence without authority isn't leadership. It is exposure.

In these environments, naming a failure feels impolite or "political." Because no one owns the outcome, the definition of success becomes strangely negotiable. We stop asking "Did we achieve the ROI?" and start asking "Is the trendline moving?" The organization learns to live with chronic under-delivery because there is no single point of failure—only a distributed, polite decline.

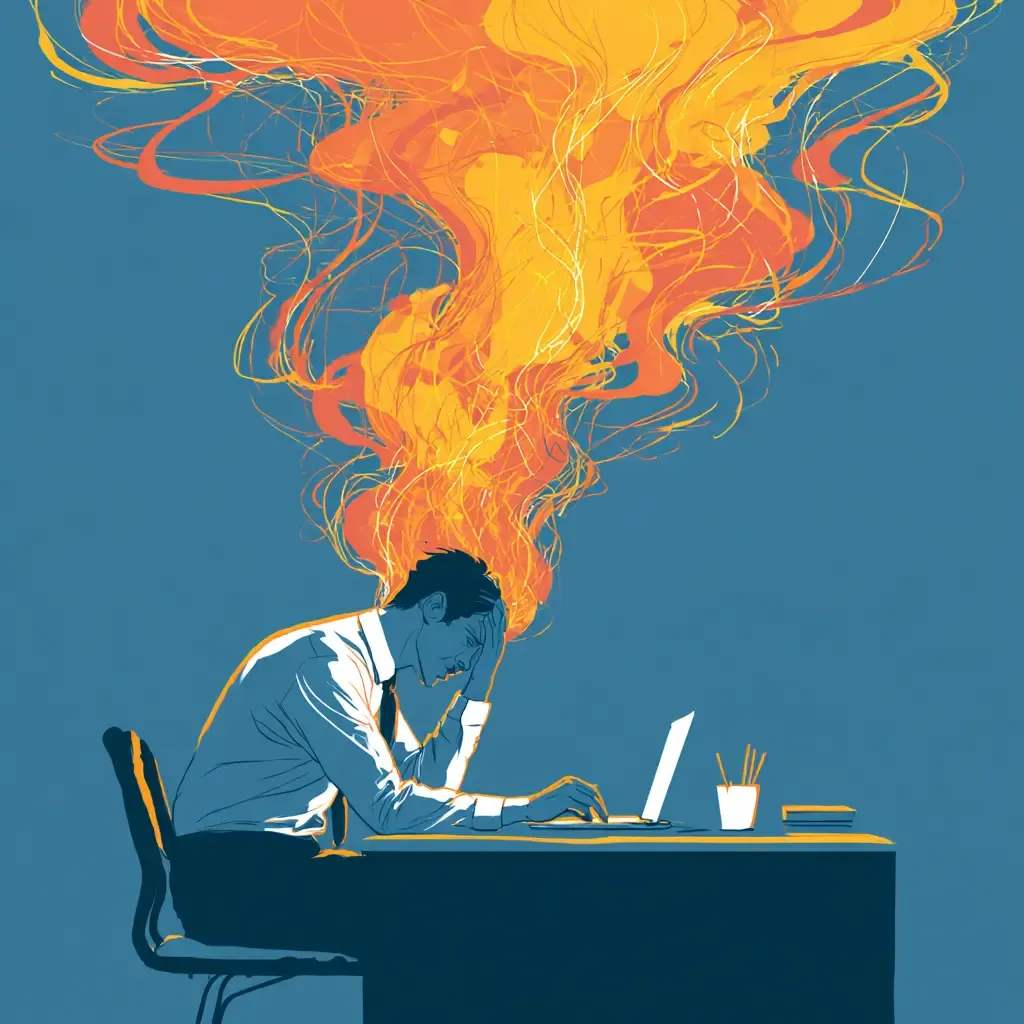

4. The Defensive Crouch

Over time, this lack of clarity hardens into culture. Leaders stop expecting clean ownership because they haven't seen it modeled. Teams learn that survival depends more on narrative management than on actual delivery.

At this point, calling change "everyone's job" is no longer an aspirational goal. It is a defensive strategy. It is a way of avoiding the uncomfortable reality that real transformation requires someone to be answerable when things go wrong. It requires authority to be named and limits to be acknowledged.

Final Thought

If change truly belongs to everyone, then failure belongs to no one. And when failure belongs to no one, it is never corrected; it simply becomes the "background radiation" of the workplace.

The cost of shared ownership isn't chaos or rebellion—it is the slow erosion of accountability, disguised as collaboration. If your organization insists that change is everyone’s job, it’s time to ask: Who is actually allowed to make the hard calls? If the answer is "the group," don't be surprised when the change never sticks.

ChangeGuild: Power to the Practitioner™

Now What?

Identifying the "ownership trap" is only the first step. To move from diffused responsibility to clear accountability, practitioners should take these five actions:

- Audit the "Decision Rights": Before the next phase of your project, explicitly map out who has the final "Yes" and "No" on budget, process changes, and go-live dates. If the answer is "the steering committee," push for a single named executive sponsor.

- Redefine "Influence" in Your Charter: Stop accepting "influence" as your only lever. Update your project charter to include formal escalation paths and specific mandates that give the change team the authority to halt or pivot work if adoption milestones aren't met.

- Name the "Owner of Failure": In your next stakeholder meeting, ask the uncomfortable question: "If this does not achieve the desired ROI, who is the single person answerable to the board?" This isn't about blame; it’s about identifying who has the skin in the game to make hard tradeoffs.

- Shift from Sentiment to Metrics: Replace vague "sentiment" updates (e.g., "The team feels positive") with hard adoption data. When the data is tied to a specific leader's KPI, the ownership of that change becomes visible and non-negotiable.

- Stop "Narrative Management": Resist the urge to polish the status report when ownership is blurry. Be transparent about risks that stem from a lack of authority. By refusing to mask structural gaps with optimistic "influence," you force the organization to address the accountability vacuum.

Frequently Asked Questions

Doesn't change actually require everyone’s involvement to succeed?

Absolutely. Participation is not the same as accountability. While every employee must participate in the change for it to stick, a single leader must be accountable for the outcome. Think of it like a professional sports team: every player is responsible for their performance, but the Head Coach is the one accountable for the win or the loss.

Am I asking for a return to "Command and Control" leadership?

No. Accountability is actually the antidote to the worst parts of command-and-control. In a command-and-control structure, people follow orders to avoid punishment. In an accountability-based structure, leaders are given the autonomy to make decisions, provided they are willing to own the results. It is about clarity, not coercion.

How do I tell my boss that "Shared Ownership" is failing us?

Focus on the friction. Instead of attacking the philosophy, point to the symptoms: delayed decisions, conflicting priorities, or the "Influence Trap." Frame the conversation around speed and ROI: "To move at the pace the business requires, we need a single point of escalation who can make the final call on X and Y."

Can a Change Management Lead be the one who "owns" the change?

Rarely. The Change Lead owns the methodology and the execution, but the Business Lead (the one who owns the P&L or the departmental budget) must own the outcome. If the person paying for the change doesn't own the success of it, the change will always be treated as an "optional" HR or IT project.

What is the first sign that ownership is too diffused?

The "Polite Decline." If your project meetings are full of people agreeing that the change is important, but no one is willing to reallocate their team's time or budget to support it, you have a diffusion problem. When ownership is clear, leaders make hard tradeoffs; when it’s shared, they just make excuses.

Recommended Reading

This post is free, and if it supported your work, feel free to support mine. Every bit helps keep the ideas flowing—and the practitioners powered. [Support the Work]